After many starts and stops writing this entry, it is finally time to tell the story of Grand Prix Kansas City 1999. I added what I could salvage from this tournament to the site about a year ago—I have rounds 4 through 12 of the twelve rounds of Swiss, and a scattered few matches from the first three rounds. You may recall the puzzle I had to solve in order to reconstruct the Saturday matches of GP Philadelphia 2000. That was like trying to replace the batteries in an antique watch. Kansas City was like trying to put the watch back together after it was thrown into a muddy puddle and then run over by a truck. Fair warning, we’re going to have to talk about not just usual tiebreakers, but second- and third-order tiebreakers soon.

For context, coverage has come full circle in the two decades since gpkc99 (March 27-28, 1999). At the time Wizards’s official site would have coverage (“cybercasts”) for some tournaments but not all; pairings and standings for some GPs in this era were preserved because they appeared on third party sites. That might have been the tournament organizer, which is the case for gpkc99: the relevant information appeared on New Wave’s site. Other GPs, like Seattle 2000, had text coverage hosted on the Dojo. Some of those pages migrated over to the official tournament archive, but not all of them; the official coverage link for gpkc99 points to a page that only has a text recap of the top 8. I’ve dug around quite a bit looking for references to other third-party pages that might have coverage on them, but haven’t yet found any others that made their way onto the Wayback Machine. There’s a small but nonzero chance that, for example, some of the missing European or Asian GPs once had coverage posted somewhere and I haven’t had the good fortune to stumble upon them.

New Wave’s coverage archive has the suggestion of pages for other tournaments they hosted. The jewel among them is GP San Francisco 1999. Unfortunately the New Wave archive was only discovered by the Wayback Machine once, and almost all of the SF results pages timed out, so there isn’t really any hope to reconstruct that tournament like we’re about to do here. I wonder sometimes whether the .html files are still out there somewhere… I got the sense that the New Wave coverage was largely spearheaded by Alex Shvartsman, much as the Dojo coverage seems to have been orchestrated by Mike Flores in places. Is there a chance that gpsf99 is on a zip disk in his garage somewhere? I have similar questions about Pro Tour New York 1998 and Pro Tour Chicago 1998—those tournaments were at one time 100% on the internet but they didn’t migrate to the current version of Wizards’s coverage archive, and the Wayback Machine didn’t capture every page from those two events. Are they sitting on a backup tape drive in a filing cabinet in the basement of WotC headquarters?

As for Kansas City, the pages that were on the internet were captured but not everything was posted in the first place. Coverage starts with round three standings on day one, and with round 8 standings on day two. So I have pairings for rounds 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, and 12; and I have standings (including all tiebreakers) for rounds 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, and 12. Yes, the GP only had twelve rounds of Swiss, six on each day. The day two cut was to the top 64, which worked out to everyone at 5-1 or better and one lucky person at 4-0-2. There was a second, much less lucky, person in 65th at 4-0-2. You could have shown up for this event with three byes, lost two matches, found yourself dead for day two, and dropped having played less Magic than you would have played at FNM. Also note that awkwardly round 10 standings are missing: the page exists but evidently the data was corrupted back in 1999.

You’ll notice that I only said “pairings,” not “results.” The original coverage page didn’t have any results pages. This is not a deal-breaker: we can make inferences as to the results of matches based on how the numbers of match points change from round to round. (Actually, the pairings themselves had lines like

Finkel, Jon (414) 27 1 Rubin, Ben * (456) 24saying that Finkel, with 27MP, played against Rubin, with 24MP, on table 1. So the match point information is actually preserved with some redundancy.) But I also didn’t say anything about the pairings in rounds 1, 2, 3, 7, or 8. They are missing. This is a big issue. It is also in some sense the opposite of gpphi00, where we knew the pairings and didn’t know the results. That’s much easier than knowing the results without knowing the pairings. Without even having standings for the day one rounds, there’s not really any hope of recovering those, so I dismissed the possibility of recovering rounds 1-3 immediately. However I thought there was a real chance of reconstructing rounds 7 and 8 with the information we had, so let’s make that our goal.

The top 64 made day two, so there should be 32 matches in both rounds 7 and 8. The first drops didn’t occur until after round 8. This can be verified from the way the score reporter printed the standings. As an example, here’s the top line from round 8’s standings.

1 Finkel, Jon 24 75.8333 94.1176 71.7677 5/5/0/3This says Finkel was in first place with 24MP; his tiebreakers were, in order, 75.83 94.11 71.76 (we’ll learn about these soon); and then the last entry “5/5/0/3” says he played five matches, winning five, zero draws, and three byes. (From this you can deduce zero losses.) After round nine there are some people with lines like “7/4/0/1” implying they only have eight rounds’ worth of results and thus must have dropped before round nine. But the round eight standings show everyone in the top 64 as having played eight matches. So at the start of this project we’re 0/64 on matches deduced.

That’s a lie. Both round 7 (Paschover vs. Finkel) and round 8 (Price vs. Maher) had a feature match with text coverage, so there’s two matches where we know who played whom. Also there are eight surviving tournament reports from archived snapshots of the Dojo which were written by people who made day two. Unfortunately a couple of the authors didn’t know the names of some of their opponents, or elected not to include them. Still, after this free information, we are at 14/64. (Also those tournament reports got us a couple of matches from rounds 2 and 3… I’ll take whatever I can get!)

For several people we can see that their after-round-8 match point total is either six more than their after-round-6 match point total, or is equal to their after-round-6 match point total. In that case we know that they won both their matches or lost both their matches, but we don’t know against whom. We also have some “loose ends,” half-finished players for which we know one of their opponents but not the other. It’s time to get our hands dirty.

Magic tournaments track three tiebreakers. The main one, which is what is usually meant when someone just says “tiebreakers,” is the average of your opponents’ match win percentage. (This is called OMW, abbreviatng “opponent match win%.“) For each opponent, calculate the ratio [player’s MP] / [3 × rounds played], and then average those ratios. The result is the OMW. The only additional wrinkle is that a number less than 1/3 gets replaced with 0.3333. Here’s how we can leverage tiebreakers to discover something about missing opponents. This is Jon Finkel’s opponents and their records after round 8. Note Jon had three byes.

R4 Jamie Parke 4-2 R5 Jacob Welch 5-3 R6 Gary Krakower 6-2 R7 Marc Paschover 7-1 [known from feature match] R8 [unknown]

tiebreaker (omw) 75.8333 [known from R8 standings]

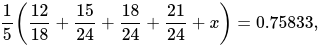

Okay, to be fair, we can deduce that Jon’s unknown opponent is also 7-1 without doing math, since he should have been paired against another 7-0 player in round eight and he won. But still, let’s see how this is done with tiebreakers. The information in the table above leads to the equation

where x is the match point ratio of the unknown player. Solving the equation gives x = 0.87499. We know in this case that x should be a fraction of the form y/24; solving y/24 = 0.87499 gives y = 20.9998, so up to a rounding error we get that the unknown opponent had 21 match points, so was 7-1 after round 8.

Is this even good? There were sixteen people who were 7-1 after round 8, so all we know is that Finkel’s opponent was one of those. (There are a couple we can rule out: it isn’t Paschover, since they played round 7, for instance. A couple of them also have opponents known from tournament reports.) There are two ways we can proceed. We know Finkel’s opponents going forward and we know the tiebreakers after future rounds, so we can learn extra information about the unknown round 8 opponent by looking into the future. Here’s the situation after round 9. Note Welch, Krakower, and Paschover make different contributions now than they did before since they played in round 9.

R4 Jamie Parke 4-2 R5 Jacob Welch 5-4 R6 Gary Krakower 7-2 R7 Marc Paschover 7-2 [known from feature match] R8 [unknown] R9 Lan D. Ho 8-1

tiebreaker (omw) 74.0741 [known from R9 standings]

A calculation like before says that the unknown player’s match win percentage is 0.7777, so they’re 21/27, or 7-2. This shrinks the pool of possible players from 16 down to 7, as now we need someone who went 7-1 into 7-2. Since we don’t have round 10 standings we don’t get information about the unknown opponent’s record after R10, but we can learn R11 and R12 from the extant data. This “signature” of a player’s R8, R9, R11, R12 records often identifies them uniquely, or at worst will make them a member of a set of at most two or three people. It’s possible that there will be two people with a given signature but we know the R7 and R8 opponents for one of them, and if that happens then the fact that the signature wasn’t unique won’t actually hinder us.

Let’s look at the second way to accomplish this, with the second and third tiebrekaers. The second tiebreaker is your own game score: it’s the number of “game points” you have earned divided by three times the number of games you played. Game points are like match points; you earn three points for a win, one point for a draw, and no points for a loss. As such a 2-0 win counts as 6/6 game points, a 2-1 win counts as 6/9, etc. Draws are annoying for game scores, since it depends on reporting the correct kind of draw. If you draw because game three didn’t reach a conclusion, that’s a 1-1-1 match result, so 4/9 game points. If you ID, that’s an 0-0-3 match result, so 3/9 game points. If you draw because game two finishes in extra turns and you don’t get to start game three, that’s a 1-1 match result, so 3/6 game points. This never matters in practice, but in doing tiebreaker math for other events I’ve noticed that occasionally you can only get the game score to work out correctly if you use a different flavor of draw than what’s presented in the results page.

The final tiebreaker is the average of your opponent game point percentages. (This is OGW, for opponent game win%.) As with match points, there is an artifical floor of 0.3333 imposed on your opponents who have own game scores below that percentage. The second tiebreaker will report a number less than 1/3, but the number that gets used in the third tiebreaker calculation will be inflated to 1/3 in those cases. Let’s look at Finkel again post round 8, this time examining the game scores of his opponents. Usefully the game scores can be read off of the round 8 standings, since those are the second tiebreakers. So we don’t have to try to reconstruct game scores for all the previous matches in order to use the third tiebreaker.

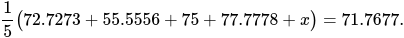

R4 Jamie Parke 72.7273 R5 Jacob Welch 55.5556 R6 Gary Krakower 75.0000 R7 Marc Paschover 77.7778 [known from feature match] R8 [unknown]

tiebreaker (ogw) 71.7677 [known from R8 standings]

This means that, like before, the opponent’s game score percentage solves the equation

The solution is x = 77.7778. Now we are looking for someone whose own game percentage (second tiebreaker) is 77.7778 and who has 21 match points after round 8. There are only three such people: Tony Tsai, Craig Dushane, and Marc Paschover (who is ineligible to have played Jon round 8). We can go deeper and reach a conclusion now: Tsai entered day two at 6-0 and Dushane entered at 5-1. We know that Jon played another 7-0 and beat them, since Jon winds up on 24MP and tiebreakers showed his opponent ended up at 7-1. Therefore only Tony Tsai could have been Finkel’s opponent. It took seven paragraphs and ~1000 words, but we now are 15/64.

Did you notice that there was something special about Jon Finkel that made the calculations possible? Puzzle that for a paragraph.

To recap, there are two different pairs of information that can help shed light on unknown opponents: we can use the combination of the first tiebreaker (OMW) together with players’ match points, or we can use the combination of the third tiebreaker (OGW) with the second tiebreaker (the games equivalent of match points). Using these, we can build a signature of the unknown opponent’s record in future rounds. Eventually hopefully this process will narrow down the set of possibilities to one player, or at least one player among those that are unaccounted for. We started with several “loose ends” since we knew only one of the two opponents for several players who happened to have played one of their rounds against someone who wrote a tournament report. We pray that filling in loose ends will create other loose ends and we will eventually untangle all 64 missing pairings.

The thing that was special about Jon Finkel is that he had three byes, so we had otherwise total knowledge about all his other opponents. Let’s jump from Finkel to Tony Tsai now. He only had two byes. Here’s what we know about his tournament so far. (Remember, annoyingly, we don’t have R7 standings.)

R8 record R8 game pct R3 [unknown A] R4 Danny Speegle 3-2 60.0000 R5 Mike Caselman 4-2 56.2500 R6 Devon Herron 6-2 68.4211 R7 [unknown B] R8 Jon Finkel 8-0 94.1176

R8 tiebreakers 71.1111 66.2500 [omw / ogw]

How can we make progress when there are two variables in the equations? Don’t forget that we have information after round 6, too! The best possible result for us is if Tony’s round 3 opponent did not make day two. If that’s the case, then the record of the unknown round 3 opponent will not change between round 6 and round 8, and the first line of blanks will get filled in, ready for use in the round 8 calcuations. With this in mind let’s strip off rounds 7 and 8 and look at the end of day one standings.

R8 record R8 game pct R3 [unknown A] R4 Danny Speegle 3-2 60.0000 R5 Mike Caselman 4-2 56.2500 R6 Devon Herron 5-1 71.4286

R6 tiebreakers 65.0000 60.8085 [omw / ogw]

From this table we infer that Tony’s round 3 opponent had a .5000 match win percentage (either 2-2 or 3-3, we can’t tell but it doesn’t matter) and a game win percentage of .5556. Usefully, they did not make day two. So their contribution isn’t going to change between rounds 6 and 8. We can go back to the first table and fill in the static information about unknown A, leaving us only with unknown B to consider.

R8 record R8 game pct R3 [unknown A] 2-2, say 55.5556 R4 Danny Speegle 3-2 60.0000 R5 Mike Caselman 4-2 56.2500 R6 Devon Herron 6-2 68.4211 R7 [unknown B] R8 Jon Finkel 8-0 94.1176

R8 tiebreakers 71.1111 66.2500 [omw / ogw]

This table implies that unknown B was 6-2 after round 8 and had a 63.1555 game score. Only one person fits that bill: Justin Holt. Since both entered day two at 6-0 and Holt is now 6-2, the result of the round 7 match was a win for Tsai. 16/64! (As a footnote, nobody after round six had nine match points and a 55.55 game score. But there were fourteen people who were 2-2 with that game score. Since they dropped after round 4 there’s not much hope of figuring out who they were.)

What would we have done if Unknown A had made day two? I think the only logical options are panic and despair. The problem in that case is that the contribution that Unknown A would have made to the round 6 tiebreakers will not match the contribution they make to the round 8 tiebreakers, so learning where they were after round 6 isn’t particularly helpful. Many of the players who made day two had one or zero byes, so in place of our single mystery player we would calculate from the round 6 standings a sum of two or three mystery players’ statistics. If the stars align and none of them made day two, then their agglomerated tiebreakers will contribute the same amount towards round 8, and we can then isolate the single missing person just like what we did for Tony.

You should probably be asking right now, if we’re in a situation where there are multiple unknown day one opponents getting clumped together, how would we know whether any of them made day two in the first place? It shows up when you try to calculate the unknown day two opponent’s information from tiebreakers. We’re expecting to see the unknown player have a match win percentage of .8750 for a 7-1 record, .7500 for a 6-2 record, or .6250 for a 5-3 record. (A couple of players have draws, but let’s ignore those for now and say these are the only options. Two players were 8-0 and we have them taken care of.) Suppose we infer a match win percentage of .8525 instead; that would imply 20.46 match points out of 24. That’s bad news. A result like that means that something is wrong upstream—someone from day one is making a different contribution to round 8 than they did to round 6. Unfortunately that player’s tiebreakers are then useless, since we can’t isolate the signature of their unknown day two opponent. I didn’t calculate tiebreakers for everyone, since both opponents were already known for whatever reason for several people at this point. Of the players I did calculate, eleven had useless tiebreakers. This adds a level of suspense to our excavation effort, since at the bottom of our well is now a swill of uncertainty.

I mentioned draws in the previous paragraph. There were six people whose round 8 match points differed from their round 6 match points by 1 or 4. Those people had to have played each other in at least one of their matches. For a couple of them one of their non-draw result was known, and so then that forced their other match to be a draw. The location of the six draws was comparatively easy to isolate.

You may recall that our over-arching plan was to pull on loose ends (players for which one of their opponents’ identites is known) until our knot untangled. I have sad news: we won’t get to the finish line this way. At some point in the high 30s I got stuck; all the loose ends involved people with useless tiebreakers, so I needed one new idea to get to the end. Let’s look at Eric Lauer, who had three byes but didn’t have either of his opponents’ identities uncovered up to this point. He goes from 5-1 after round six to 6-2 after round eight.

R8 record R8 game pct R4 Brent Parr 7-1 75.0000 R5 Devon Herron 6-2 68.4211 R6 Joel Noble 4-2 61.5385 R7 [unknown A] R8 [unknown B]

R8 tiebreakers 75.8333 66.2551 [omw / ogw]

The goal is to try to tease apart the two missing data points from their sum. For match win percentage, the contribution of A+B is 1.5 in aggregate. Multiplying by 24 tells us that A+B had 36 match points altogether. Either they were both 6-2 or one was 7-1 while the other was 5-3. Assuming that there aren’t any pairdowns, the first situation can’t occur! This is because Lauer either goes WL or LW. If it’s WL, then opponent B plays him in round eight where both are 6-1, and Lauer loses, so B winds up 7-1. Otherwise opponent B plays Lauer in a round eight match where both are 5-2, and Lauer wins, so B winds up 5-3. It’s impossible for B to be 6-2.

There aren’t many 7-1 slots to go around at this point, so this is possibly useful already. Even more powerful is to look at the aggregate contribution of the game win percentages. The contribution of A+B to OGW is 126.30. I then wrote a program in Python to look at every possible way that two own game scores (second tiebreakers) could add up to 126.30, and it turns out that the only pair among the ones that were left with unknown opponents at that point is 68.42 + 57.89, and only Jeff Matter has a 57.89 second tiebreaker. Even better, only John Lagges has the combination of a 68.42 second tiebreaker plus a 7-1 record. (Nobody has 68.42 + 5-3.) So now we know that Lauer plays Matter + Lagges in some order. This potentially gets us un-stuck, since now both Matter and Lagges are “loose ends” as one of their opponents is known. We just don’t know whether Lauer plays them in round 7 or in round 8. Further down the line this thread of reasoning hooked into someone with useless tiebreakers, for which one of their opponents was already known. That then cleared the uncertainty of the order of the matches and snapped everything we had done so far into place.

These ideas plus a lot of patience were able to determine all 64 matches. My first attempt at this didn’t go well because I think I made some pretty shaky logical conclusions from useless tiebreakers somewhere early on in the process. For my second, successful attempt, I tried to be meticulous in note-taking so that I would have multiple save points in case something went south. Here’s my main thread of notes (PDF), containing the 64 matches deduced in order. Here you can see my furious scribbling (JPG) trying to work out information about unknown opponents; this goes on for several pages. In the image you can see me working out the records for an unknown opponent in future rounds (boxed in each table). Sometimes I’m able to figure out the identities. For others, OGW calculations had it limited to a couple of people before I started—you’ll see in the table in the middle that Ferguson’s R8 opponent was either Stanton or Lewis, and the fact that the unknown opponent made OMW contributions of 18/24 and 18/27 in rounds 8 and 9 meant it must have been Lewis. Most of these calculations wound up in a spreadsheet that I used to track my progress.

I should add that there are two other places where I had to use this technique to recover lost pairings: GP Kuala Lumpur 2000 round 10 and Pro Tour Los Angeles 1998 round 4. These were significantly easier due to (a) having total information about all previous rounds and (b) only needing to reconstruct one round instead of two consecutive rounds. ptla98 R4 is the only one of these that took place on day one, so at the lowest tables we are trying to determine identities of players who had 0-3 records. This is typically impossible because the .3333 floor artifically obfuscates players’ identities. Still, I was able to recover 156/164 matches, which I’m treating as a win. I believe that I could reconstruct all of the missing days of ptny98 and ptchi98 if I had the standings after each round, but sadly the standings are on the tape drive backup in the basement right next to the results and pairings. I’m hoping I never have to do this again, though if it means more data on the site and we come across data that needs to be rebuilt I’m absolutely up for the challenge.